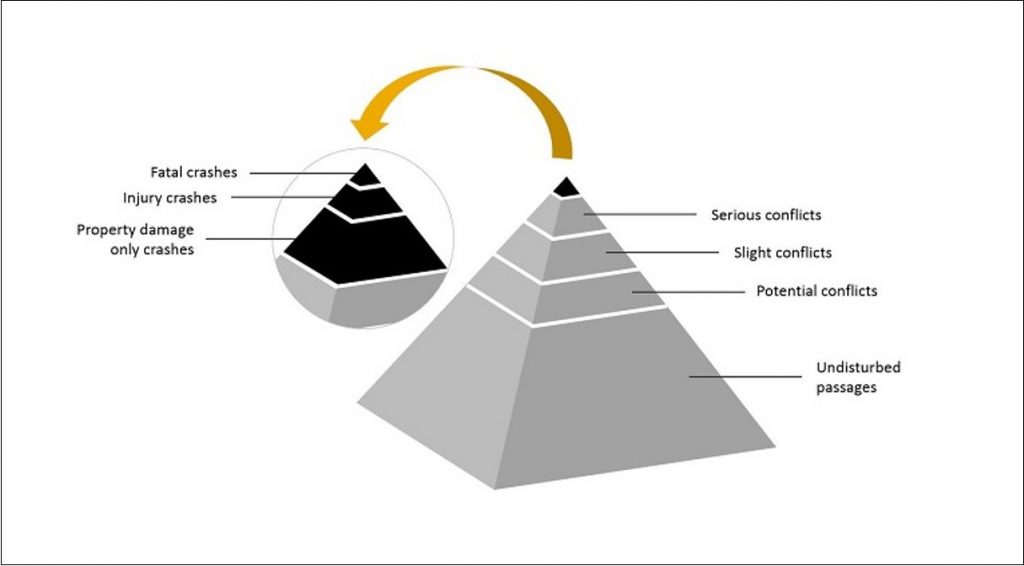

In every interaction between two road users, factors such as drivers’ inattention, road surface, vehicle conditions, traffic situation, etc. have the potential to lead to a crash (Reason et al., 2006). This means that in the case of a collision, the crash might not have taken place if all crash-potential factors were not present at the same time. The same logic can be applied to any successful traffic encounter; if one or more factors had been different, each successful encounter between two road users has the potential to result in a collision.

With this in mind, all traffic events can be defined by how close two road users were to colliding and the severity of the consequences if the interaction were to have resulted in a crash. This is also reflected in the safety pyramid, which is widely used to demonstrate that crashes represent an extreme on the severity spectrum of all traffic encounters.

It has been recommended that any traffic events having a TTC (Time-to-collision) less than the typical human perception and reaction time (about 2 seconds) should be considered unsafe. But what does this mean for events with a TTC value higher than the perception and reaction time?

Research findings suggest that even normal traffic events contain information that can be applied to make road safety assessments. For instance, Meng et al., (2012) analyzed rear-end conflicts in two urban road tunnels in Singapore and concluded that vehicles are exposed to dangerous situations when TTC is lower than a threshold value of 2 seconds, but events with a TTC lower than 4 seconds are still meaningful for developing a conflict-crash relationship.

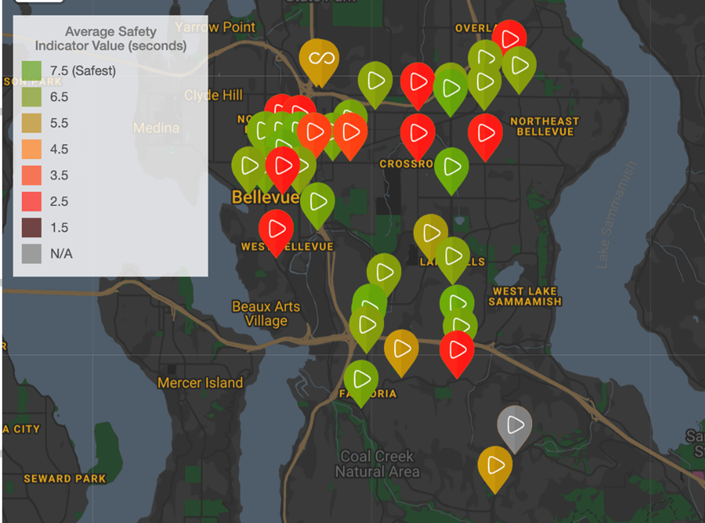

This is not limited to TTC. Songchitruksa and Tarko (2006) examined the frequency of right-angle collisions at signalized intersections using the safety measure of PET (Post-encroachment Time) and found that a PET threshold as large as 6.5 seconds gives the best-fitted model for site-aggregated crash count.